|

E-Mail Edition Volume 12 Number 2 |

|||

|

Published Spring, 2015 Published by Piccadilly Books, Ltd., www.piccadillybooks.com. Bruce Fife, N.D., Publisher, www.coconutresearchcenter.org

|

|

||

|

If you would like to subscribe to the Healthy Ways Newsletter |

Contents

|

||

|

|

The U.S. Government to Withdraw Longstanding Warnings About Cholesterol

"Cholesterol is no longer considered a nutrient of concern for overconsumption," reports the US Department of Health... Have you restricted your consumption of eggs,

meats, and dairy in fear that they might raise your blood cholesterol

levels? If so, you no longer need to worry. After years of debate about

the perceived dangers of consuming cholesterol, the nation's top nutrition

advisory panel has decided to drop its caution about eating cholesterol-laden

food, a move that could undo almost 40 years of government warnings

about its consumption. Every five years, the United States Department

of Health and Human Services updates a set of Dietary Guidelines

intended to help Americans make healthier food choices. These guidelines

also help establish regulations and standards food companies follow

in labeling their products. The 2015 edition will mark perhaps the biggest

change since the original 1977 Guidelines by dropping the warning about

cholesterol consumption. One of the six core goals since the 1970s has

been to limit the intake of cholesterol to less than 300mg per day,

however the present Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) believes

that cholesterol consumption is no longer something we need to worry

about. The group's decision follows an evolution of

thinking among many nutritionists who now believe that eating foods

high in cholesterol may not significantly affect the level of cholesterol

in the blood or increase the risk of heart disease. Blood cholesterol

level is carefully regulated and is not haphazardly influenced by diet.

This is why dietary approaches can alter blood cholesterol by less than

10 percent. The amount of cholesterol produced within our bodies every

day is much larger than what we get from our diet. Therefore, the amount

we consume has no significant bearing on blood cholesterol levels. Foods high in cholesterol — such as eggs, red

meat, and seafood — have long been considered contributors to the risk

of heart disease. Years of research seeking to establish a possible

causative link between them and undesirable health outcomes has been

a failure. In the absence of a proper scientific consensus and given

that the human body produces a lot more cholesterol than it takes in

via the diet, the DGAC has decided that "cholesterol is not considered

a nutrient of concern for overconsumption." Therefore, the amount of

it that you consume is no longer thought to be important enough to restrict. While Americans may be accustomed to conflicting

dietary advice, the change on cholesterol comes from the influential

Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, the group that provides the scientific

basis for the "Dietary Guidelines." That federal publication has broad

effects on the American diet, helping to determine the content of school

lunches, affecting how food manufacturers advertise their wares, and

serving as the foundation for dietary advice given by doctors and government

agencies. Many nutritionists said lifting the cholesterol

warning is long overdue, noting that the United States is out-of-step

with many other countries, where diet guidelines do not single out cholesterol. "There's been a shift of thinking," said Walter

Willett, MD, chair of the nutrition department at the Harvard School

of Public Health. He called the turnaround on cholesterol a

"reasonable move." But the change on dietary cholesterol also shows

how the complexity of nutrition science and the lack of definitive research

can contribute to confusion for Americans who, while seeking guidance

on what to eat, often find themselves afloat in conflicting advice. Cholesterol has been a fixture in dietary warnings

in the United States at least since 1961, when it appeared in guidelines

developed by the American Heart Association. Later adopted by the federal

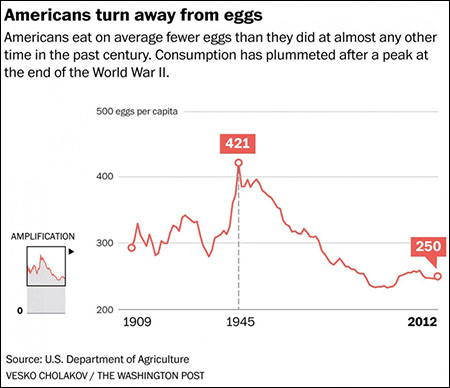

government, such warnings helped shift eating habits and dropped egg

consumption by 30 percent.

Even as contrary evidence has emerged over the

years, the campaign against dietary cholesterol has continued. In 1994,

food-makers were required to report cholesterol values on nutrition

labels. In 2010, with the publication of the previous "Dietary

Guidelines," the experts again focused on the problem of "excess

dietary cholesterol." Yet many have viewed the evidence against cholesterol

as weak, at best. As late as 2013, a task force arranged by the American

College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association looked at the

dietary cholesterol studies. The group found that there was "insufficient

evidence" to make a recommendation. Many of the studies that had been

done, the task force said, were too broad to single out cholesterol. "Looking back at the literature, we just couldn't

see the kind of science that would support dietary restrictions," said

Robert Eckel, the co-chair of the task force and a medical professor

at the University of Colorado. The previous guidelines called for restricting

cholesterol intake to 300 milligrams daily. (For comparison, the yolk

of a single egg has about 200 milligrams.) American adult men on average

ingest about 340 milligrams of cholesterol a day, according to federal

figures. That recommended figure of 300 milligrams, Eckel said, is

"just one of those things that gets carried forward and carried

forward even though the evidence is minimal." Other major studies have indicated that eating

one or two eggs a day does not raise a person's risk of heart disease. While reversals in dietary recommendations might

seem aggravating, it is a sign of progress. "These reversals in the

field do make us wonder and scratch our heads," said David Allison,

a public health professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

"But in science, change is normal and expected." When our view of the cosmos shifted from Ptolemy to

Copernicus to Newton and Einstein, Allison said, "the reaction was

not to say, 'Oh my gosh, something is wrong with physics!' We say,

'Oh my gosh, isn't this cool?' " Allison said the problem in nutrition stems

from the arrogance that sometimes accompanies dietary advice. Because

a scientific body comes to a consensus about a particular issue, some

people take this as the absolute final word on the subject and ignore

contradictory evidence and ridicule those who question the status quo.

Now all those who have shouted the warning about eating cholesterol

and criticized those who questioned this advice have egg on their face.

A little humility could go a long way. Despite the change in position about dietary

cholesterol, many people are holding on to cherished opinions that fat

and cholesterol are bad and continue to shout warnings about eating

saturated fat and the dangers of high blood cholesterol. These people

are soon to find egg on their face as well. In recent years two major meta-analysis studies

which combined all previous studies on saturated fat and diet showed

that those people who eat the most saturated fat have no more incidence

of heart disease than those who eat the least, proving that saturated

fat does not cause or promote heart disease. A new meta-analysis study published February

2015 reexamined all of the data available in 1977, when the Dietary

Guidelines were first issued, concluded that the original recommendations

were based on inadequate evidence and should never have been issued.

The report, authored by an international team of researchers, was critical

of the advice against the restriction of dietary saturated fat, which

could, with time, be another area where the DGAC seeks to modify its

recommendations. The researchers concluded that a correlation

between saturated fat consumption and coronary heart disease was just

a hypothesis without good supporting evidence when the US government

issued its Guidelines in 1977 and echoed by the UK and other countries

soon thereafter.

The dietary recommendations focused on reducing dietary fat intake;

specifically to (1) reduce overall fat consumption to 30 percent of

total energy intake and (2) reduce saturated fat consumption to 10 percent

of total energy intake. Later the recommendation for saturated fat was

reduced further to 7 percent. Dr. Zoe Harcombe of the University of the West

of Scotland and lead author of the study, stated that these recommendations

"were untested in any trial prior to being introduced," As there is

today, when these guidelines were issued there was no evidence that

eating less fat or saturated fat would improve a person's heart health.. Among the data on dietary fat consumption and

heart disease that was available at the time, there were no differences

in the number of deaths from all causes, and no statistically significant

changes in death from cardiovascular disease. Eating less saturated

fat was not shown to improve a person's heart health, even where changes

in diet led to a reduction in blood cholesterol levels. "It seems incomprehensible

that dietary advice was introduced for 220 million Americans and 56

million UK citizens, given the contrary results from a small number

of unhealthy men," says Harcombe. At the time of issuing the original 1977 Dietary

Guidelines for the United States, the committee's lead nutritionist,

Dr. Hegsted of Harvard University, admitted that the evidence base for

the restriction on saturated fat was lacking. "There will undoubtedly

be many people who will say we have not...demonstrated that the dietary

modifications we recommend will yield the dividend expected," remarked

Hegsted. But his counterargument was that there was more to gain from

switching to the recommended diet than there was to lose. Such a statement

was based more on wishful thinking than good science. The longstanding advice to increase the consumption

of carbohydrates as a way to offset the reduction in total fat and saturated

fat may now be proving Dr. Hegsted's assertion wrong as subsequent research

has now shown that

low-carbohydrate diets are more effective at promoting better health

than low-fat ones. The conclusion of the Harcombe study is clear

and to the point: "The present review concludes that dietary advice

not merely needs review; it should not have been introduced." It's remarkable

that national and international dietary guidelines, that affect the

health of millions of people, have and are being issued and vigorously

supported and defended without proper scientific evidence. In fact,

a great deal of weight in the argument against the consumption of saturated

fat has been based on the Dietary Guidelines. Anti-saturated fat proponents

have used the Dietary Guidelines as proof that saturated fat is unhealthy

and trumps all the studies that claim differently. After all, a scientific

committee representing a government body must be correct—right? Several years ago I wrote a detailed overview

on coconut oil and submitted it to Wikipedia. I included an extensive

section on the health aspects of coconut oil and meticulously backed

every statement with references to published medical studies. They posted

the article but within days most of the article was replaced, including

all of the health section. In its place was a brief statement that coconut

oil is just another saturated fat and should not be consumed, as proof

the article referenced the Dietary Guidelines of the United States and

several other countries and organizations who have copied these same

guidelines. While other parts of the coconut oil article on Wikipedia

have changed over the years, this health section has remained the same. Sources:

http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2010.asp. Whoriskey,

Peter. The U.S. government is poised to withdraw longstanding warnings

about cholesterol. The Washington Post February 10, 2015.

Harcombe,

Z, et al. Evidence from randomized controlled trials did not support

the introduction

of

dietary fat guidelines in 1977 and 1983:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015;

doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000196. Chowdhury, R., et al. Association of dietary,

circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:398-406. Siri-Tarino, PW, et al. Meta-analysis of prospective

cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular

disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:535-546.

|

||

|

|

|||

|

Drink for Your Health?

Don't Bet Your Life on It

Alcohol

may not be so healthy after all. New study exposes flaw in previous

studies. Benefits of alcohol consumption questioned. A number of studies in recent years have suggested

that moderate alcohol consumption may help reduce the risk of heart

disease and death. The idea that alcohol consumption might be good for

our health has inspired hope among drinkers. But a new study by a group

of British and Australian researchers largely squashes that hope.1

According to this new study, unless you're a woman over the age of 65,

alcohol consumption is unlikely to forestall your death. And for these

older women, the health benefits of alcohol are small. Like several previous studies, this new study

initially returned findings indicating that men between the ages of

50 and 65 might reap a small benefit from drinking 1 to 2 glasses of

alcohol a day. But those apparent benefits completely evaporated when

the researchers removed from their nondrinking "reference group" all

those people who used to drink but had stopped. |

||

|

This strange twist does more than disappoint

middle-aged men eager to believe that alcohol makes them more robust.

It also casts doubt on all the previous studies that have concluded

that modest drinkers are healthier than nondrinkers (or never drinkers). It turns out that former drinkers exhibit poorer

health and have a higher risk of death, many of whom quit drinking due

to ill health or are recovering alcoholics. Former drinkers are a much

less-healthy group than people who simply never drink at all. But researchers

often lump these former drinkers together with people who have always

been teetotalers (never drinkers). The authors of the current study

estimate that more than half of those who call themselves nondrinkers

are misclassified as never drinkers. |

|

||

|

The inclusion of these less-healthy former drinkers

makes the average health of "nondrinkers" look poorer. In comparison,

those who consume alcohol tend to look healthier. In the current study, when these former drinkers

were expunged from the comparison-group of teetotalers, the nondrinking

group suddenly looked healthier. And the bar for showing alcohol's health

benefits rose. The apparent benefits of alcohol vanished. This study suggests that the many previous studies

finding health benefits associated with alcohol consumption suffer from

the same fatal flaw. The benefits of alcohol consumption, therefore,

have generally been overstated in recent research. This is not the first study to identify this

fatal flaw in alcohol studies. An earlier meta-analysis study that reexamined

54 previous studies found that the removal of former drinkers from the

nondrinkers categories resulted in an attenuation or complete nullification

of the reported protective effects.2 This study pretty much

nullified the conclusions all of the previous studies showing benefits

to alcohol consumption. Another possible problem with previous studies

is "selective bias" of the participants. The small benefit seen in women

over 65 in this current study, even after removing former drinkers,

may have been due to this. Only apparently healthy participants free

of prevalent disease at the time of enrolment were included in these

studies. The protective effects commonly identified among the studies

may occur partly as a function of selection biases—tthe selection of

healthy participants. If so, rather than moderate alcohol consumption

being directly involved in the attenuation of mortality risk, it may

simply represent an unidentified lifestyle trait specific to healthier

people. References

1. Knott, CS, et al. All cause mortality and

the case for age specific alcohol consumption guidelines: pooled analyses

of up to 10 population based cohorts. BMJ 2015;350:h384. 2. Fillmore, KM, et al. Moderate alcohol use

and reduced mortality risk: systematic error in prospective studies

and hypotheses. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17(5 Suppl):S16-23.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Do you have friends who would like this newsletter? If so, please feel free to share this newsletter with them.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you by a friend and you would like to subscribe, click here.

Copyright © 2015, Bruce Fife. All rights reserved.

|

|||